This issue of Lost States, through several parts, will chart the rise, and fall of one of Europe's, and the world’s, most powerful lost states.

Europe's Forgotten Terror

In 1943, Winston Churchill said, "Prussia is the root of all evil.' For men like Churchill, who came of age during the late 19th and early 20th century, Prussia undoubtedly really did embody a sort of terrifying Teutonic militarism. However, the fact that a now extinct state, based in a resource poor part of what today is called Germany, came to occupy this boogie man like role in European geopolitics, was not a foregone conclusion.

Five hundred years earlier, the duchy of Prussia wasn’t someplace most other European powers were scared, or even aware, of. One of over 400 German speaking states, and a small, rural and disparate collection of low quality marshy land along the Baltic coast in what is now Lithuania and Poland, 16th century Prussia was a geopolitical minnow. Founded by Teutonic knights who broke away from the Hanseatic league in 1525, Prussia’s first problem was its geography.

Even after unifying with the German territories of Brandenburg in 1618, Prussia had no natural resources, poor quality agricultural land, and a location that put it between the powerful kingdoms of Sweden and Poland to the north and east and other German states to the west. As a result, if you were to pick a 17th-century German state likely to dominate the rest, Prussia would not have been it.

Ravished By Swedes

During the 30 Years War, which also began in 1618, Prussia's geography became an existential issue. Throughout the war, the duchy’s newly incorporated territories of Brandenburg were occupied by various marauding armies. Thanks to some poor diplomacy on Prussia's part, its territories were intermittently attacked and ransacked by all sides in the conflict, including the powerful kingdom of Sweden.

The effect of this chaos was such that by the War's end in 1648, over half of Prussia’s population had either been killed or had emigrated. The capital Berlin, was left with only 6000 inhabitants - less than 10% the size of Hamburg at the time, while in rural areas, the population was only around a third of its pre-war size.

The story of how Prussia rose from this point to become one the world's most powerful states shows that, with good governance, clever diplomacy, and a thirst for power, states can sometimes overcome natural disadvantages.

Saved By Taxation

In 1640, a Hohenzollern prince from Brandenburg, Frederick William, "the great elector," ascended to the Prussian throne. Keenly aware, thanks to a childhood spent locked in a fortress, of the humiliation his state had recently undergone, Frederick William did several things that changed the course of Prussia's history.

Firstly he raised a large professional army that existed outside the control of noble estates. This forward-thinking undertaking (at the time, most European armies consisted of either peasant conscripts provided by wealthy families or mercenary bands) also required reforming taxation - the army would quickly grow to take up half the state's budget.

Meeting this burden meant that every Prussian subject now had to contribute to the states coffers, a situation which also meant a loosely region connected now had something, taxation, to tie it together. And due to the need to manage taxes efficiently, bureaucracy evolved. Inspired by time spent in Holland, Fredrick also invested in an efficient transportation network, namely through canals (many of which are still in use today) to connect his Duchy's many landlocked territories.

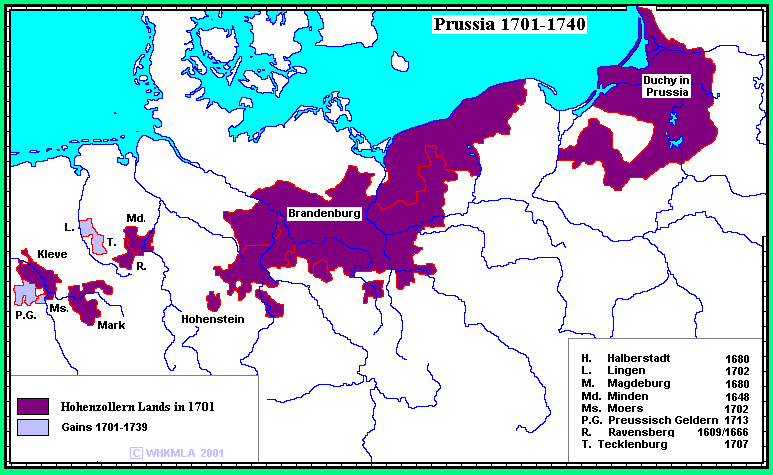

The Great Elector later used his taxation-powered army, and more efficient state, to great effect against the Swedes, the Polish, and various other foes. Before long Prussia's territory expanded significantly. Flushed by these military successes, Prussia became a Kingdom in 1701 and was now one of Germanies largest states.

A Modern Army With Giant Soldiers

Under the Great Elector, the toolkit for Prussian success was created; put together a big army and fund it with an efficient state. The Great Elector's son, Frederick the First, added to this recipe, throwing in a few ingredients of his own. Through forceful conscription of peasants and nobles, he eventually turned the Prussian Army into the fourth-largest standing army in Europe - despite Prussia only having the 12th largest population at the time.

Frederick also embodied a sort of distinctly Prussian military fetishism. Rarely wearing anything other than an army uniform (of his own design), he spent most of his time tinkering with his armies. On one level this meant adopting the latest military technologies, like flintlock muskets and regimental drills, however on another it also took on an perversely aesthetic dimension. Under threat of draconian punishments, he required that in certain regiments, soldiers must either have a uniform length of facial hair or paint it on if they cannot grow it.

Strangely he also began purposefully recruiting, and even tried to breed, an army of gigantic soldiers from around the world (each recruit was over 6ft 2 - a tremendous height at the time) known as the Potsdam Giants. Talking to the French ambassador at the time, the Prussian king (who was himself 5ft 3) reportedly said "The most beautiful girl or woman in the world would be a matter of indifference to me, but tall soldiers—they are my weakness".

Critically for Prussian history, however, "the soldier king" didn't actually engage his carefully crafted army in any serious warfare. Instead, he begat Prussia, a massive modern army that was among the most well trained and technologically advanced in Europe. This resource would be used to tremendous effect by his heirs, one of which, his Grandson, was another Fredrick but whose prefix was "Great."

In the next part of this issue of lost states, we will look at what happens when an effeminate, tolerant, and liberal king takes charge of one of the world's most effective armed forces - don't miss it.